It’s a common enough greeting. Often followed by a short, quick, stock answer of ‘I’m fine’ or (if you live in the UK), ‘not too bad’!

But how are you really feeling?

The thoughts we pay attention to (and more likely to act upon), are elevated by the underlying feelings and emotions we have at the time. Leaders who understand how our feelings and emotions direct our physiological state can help create an emotionally agile workforce that’s better equipped to respond to stressful situations and increase performance.

We have an ancient brain being put into modern work situations and a world of media multitasking. And yet, our modern brains retain a primitive and evolutionary life-saving threat detection system, which is constantly scanning the world for danger and problems that require our attention.

Many situations feel ‘dangerous’ and trigger our survival fight or flight response. But instead of a lion chasing us, it may be a manager who comes to you with last-minute urgent requests on top of an already heavy workload. Similarly, it may be a lack of psychological safety at work, not feeling valued, a threat to your status, or a lack of trust in the workplace.

In this article, we look at how the nervous system guides our behaviour and explore the value of polyvagal theory (the role of the vagus nerve in emotion regulation, social connection and the survive response). We share an understanding of how this can help support emotional agility; a key ingredient of being in a state of ‘thrive’. In this state, leaders can make better decisions, be more focussed, creative and can build higher trust, rapport and connection.

Evidence by Paul Zac et al (2017) shows that when trust is high, organisations have a workforce that is 74% less stressed, has 106% more energy, 60% more joy, 70% more purpose, is 50% more productive, and has 50% more retention.

Who wouldn’t want that?

The Autonomic Nervous System and Polyvagal Theory

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) functions as our built-in threat detection system, constantly scanning our internal and external environment for cues of safety and danger every microsecond. This happens below the level of consciousness, prior to any rational thought process.

Our emotional and intuitive (limbic) response is three times faster than our rational thinking (prefrontal cortex) response. So, our ’thinking’ brain doesn’t kick in to work out what has happened and what to do about it; until after the threat signal has already triggered a physiological response, again, the fight, flight or freeze response.

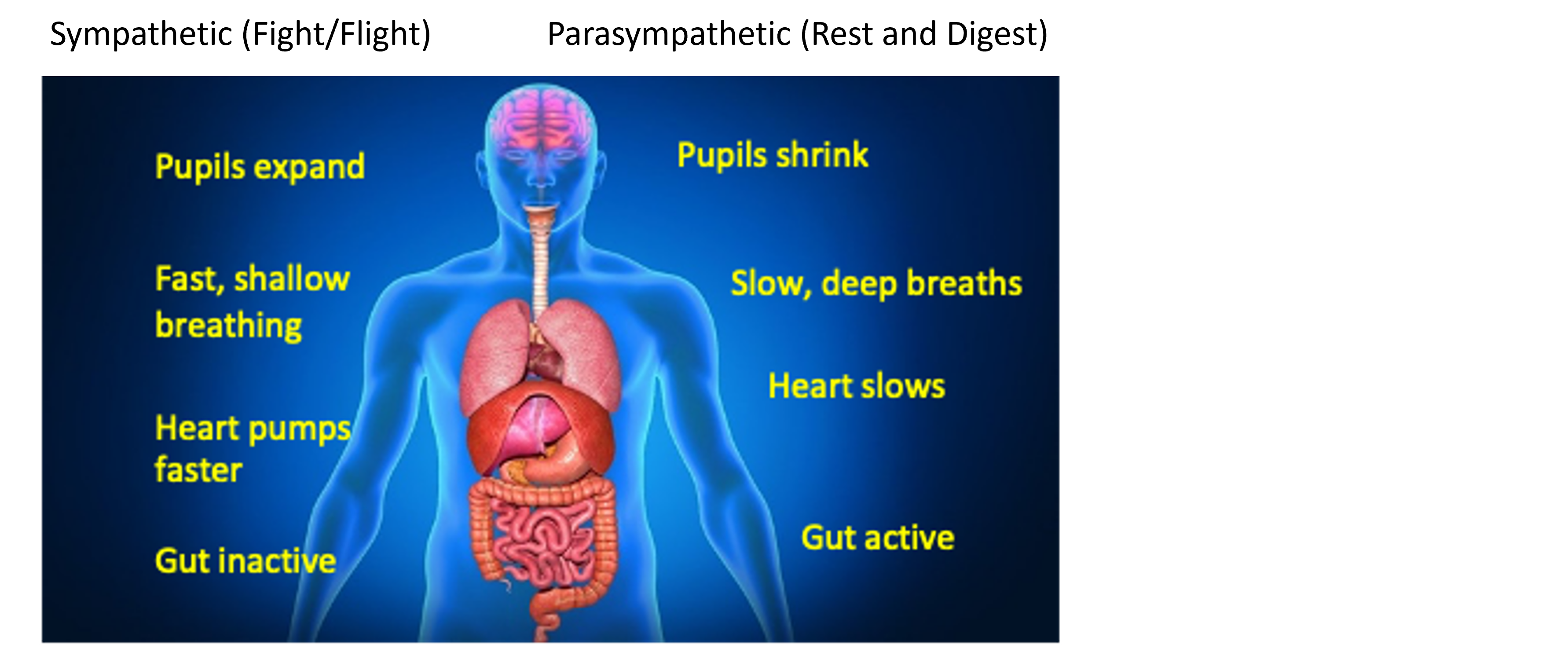

The traditional view of the nervous system is presented in two-parts (Fig 1), the sympathetic division, which deals with any kind of arousal or mobilisation which triggers an immediate survival response (fight, fight or freeze) and the parasympathetic division, which controls the body when resting or in a state of calm.

Figure 1: The Autonomic Nervous System

Polyvagal Theory (Porges 1994) identifies a third nervous system response and views the parasympathetic nervous system as being split into two distinct branches: a primitive (dorsal vagus) and more modern, (ventral vagus) branch. The modern branch plays a role in social engagement and connection. Each system is adaptive in its evolution.

Polyvagal Theory (Porges 1994) identifies a third nervous system response and views the parasympathetic nervous system as being split into two distinct branches: a primitive (dorsal vagus) and more modern, (ventral vagus) branch. The modern branch plays a role in social engagement and connection. Each system is adaptive in its evolution.

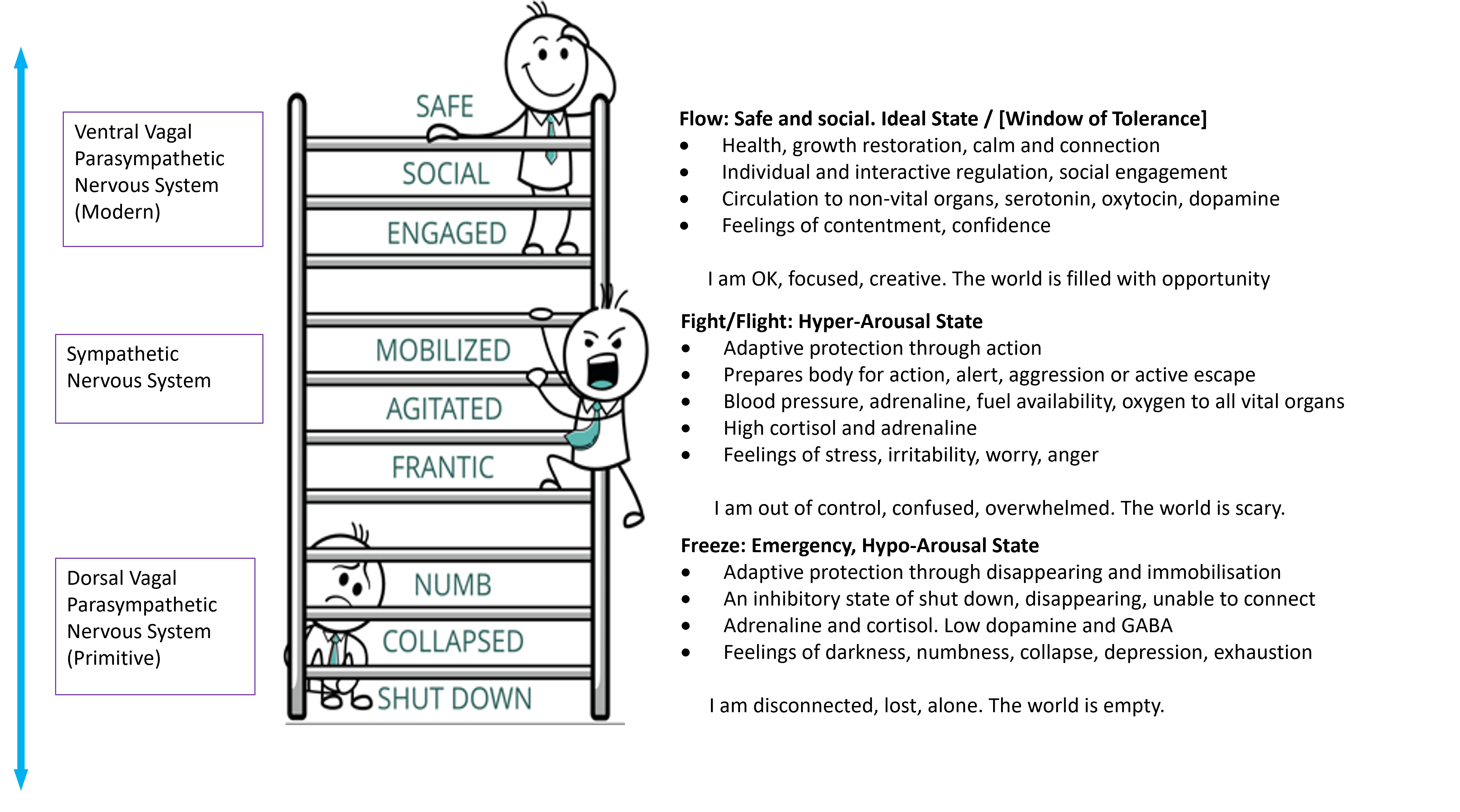

How both, the ANS and the additional lens of the Polyvagal Theory can be used in the workplace is best represented by the ladder in the work of Deb Dana (2018) (Fig 2).

This ladder talks about three states you can be in at any time throughout the day. The value is in asking yourself where you are on the ladder, and if you are in a survival state, what your triggers are and how you can move back into a state of thrive.

- If you are feeling relaxed, calm, grounded, resilient, confident, in control – or in any of your thrive emotions (trust/excitement), you are in an ideal/thrive state. This is your parasympathetic (ventral vagal) state.

The term; ‘window of tolerance’ (Dan Siegel 1999), can also be used to describe this state. It is a zone, or window of optimal energy, optimal arousal and optimal performance. Your body releases feel-good hormones; serotonin, dopamine and oxytocin, which help reduce stress and allow for learning and growth.

- If you are feeling stressed, overwhelmed, confused, anxious or in any of the survive emotions, (fear, anger, disgust, sadness, shame)- you are in your sympathetic fight or flight state, a state of hyper-arousal. Your body releases the stress hormone cortisol and adrenaline – ready for action.

- If you are feeling helpless, hopeless, exhausted, numb, or are in any of your survive emotions (mentioned above) – you are in your parasympathetic (dorsal vagal), freeze state, a state of hypo-arousal or shutdown.

While it is natural to be at different positions on the ladder it is not healthy or productive to be lower down the ladder for extended periods. States of hypo- and hyper- arousal shrink your ‘window of tolerance’ and your ability to perform, think creatively or rationally. Your ‘thinking’ brain (prefrontal cortex) is offline.

Figure 2: Adapted from The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy by Deb Dana (2018)

Stress and Building Resilience

When the ANS functions well to accurately assesses safety and danger and responds appropriately, it moves fluidly between the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions, like a pendulum. It is flexible and resilient.

“Resilience is an outcome of being able to flexibly navigate the autonomic hierarchy,” Stephen Porges (1999)

Issues mainly arise when one is ‘stuck’ in states of survival which can be caused by chronic stress.

There are no ill effects from short-term responses to stress (survival value), but longer term or chronic stress or trauma can keep our ANS from functioning in a healthy, regulated and resilient way.

In 2021, on average, 46% of the global workforce reported stress in their working day, (52% in the UK). Seven out of ten people reported feeling burnt out. In these lower-order autonomic states, our executive function is compromised, our emotions are more volatile, and we have a harder time focussing, making decisions and listening to self and others. We rely on automatic, habitual behaviours, rather than ones of innovation or curiosity.

It is through our modern social engagement (ventral vagal) system that we learn to temper our responses to modern day stress or threat. Leaders who are not just aware of their own feelings (and how to return to thrive states), but also those of the team, will be able to keep team members within their window of tolerance for longer and create a human-centric environment based on trust, where employees feel safe and can thrive.

Ask your team – how do you feel? Where are you on the ladder? In a post-Covid, world, with more remote working, it’s important to focus on this kind of thinking in team and 1-1 check ins. Good leaders look to create thrive states in others on purpose and look to expand their own and others’ window of tolerance to support creative thinking and team performance.

How to help strengthen your ‘ideal state’ and expand your window of tolerance

- Breathe – Slow down, to speed up

In the moment, in a meeting where you are triggered by another individual or at any other time, just stop and take a breath. Taking a pause, a big sigh, an elongated exhale, square breathing, or deep (belly) breathing can stimulate the ventral vagus nerve and can help us shift from the sympathetic (threat) reaction to the parasympathetic, (rest and digest) response.

“Controlling the breath, is a pre-requisite to controlling the mind and the body.” Swami Rami

- Observe – notice what’s going on in your body and notice your triggers

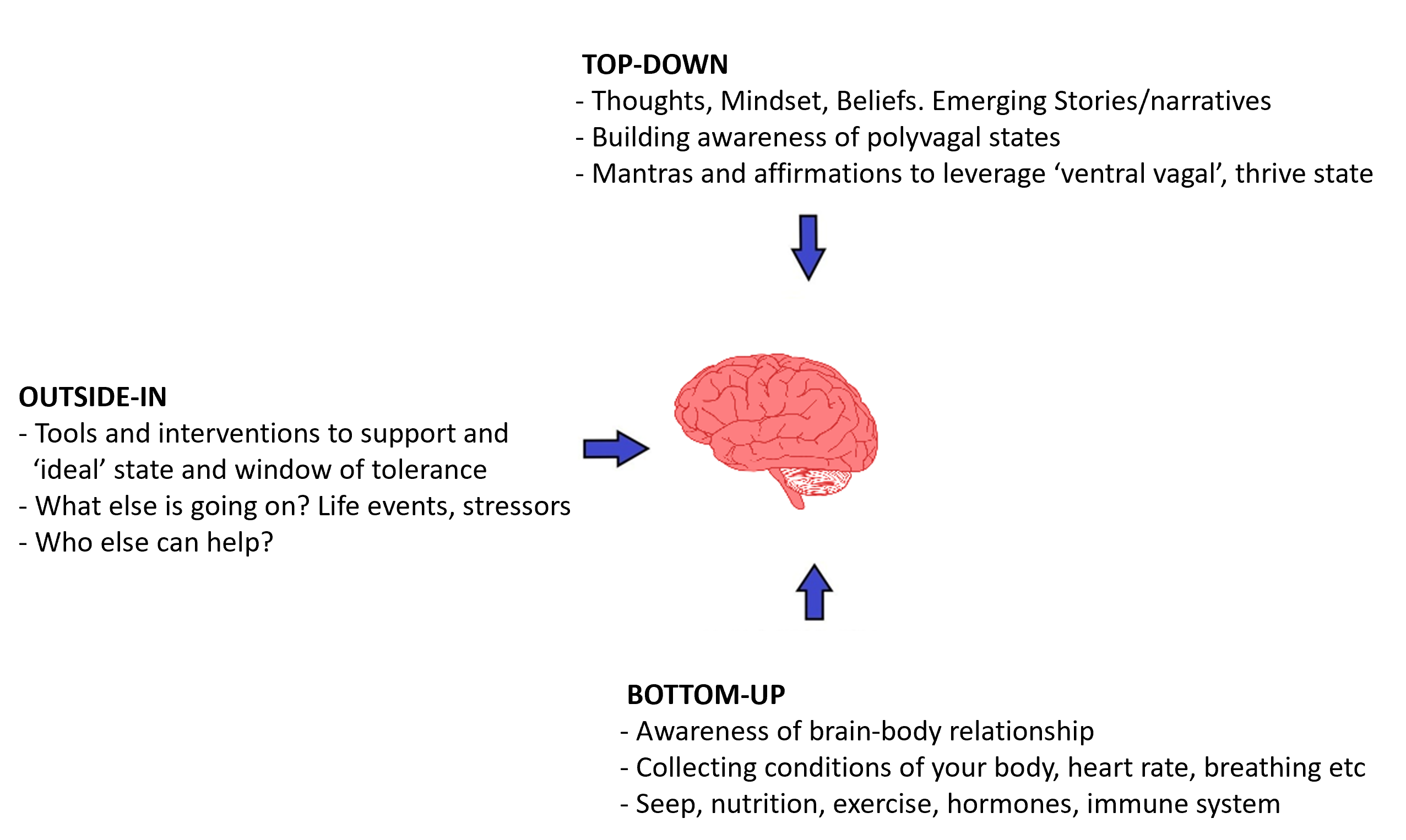

Check in with yourself. Where are you on the ladder? Is your heart rate elevated? Are you feeling tense/holding stress somewhere? In what circumstances do you experience dysregulation? Is it a certain individual? A threat to your work status? What else is going on in your life? Consider a bio-psychosocial model of your triggers (Figure 3). Expand your thinking to the wider team.

3. Connect – to self and others to build resilience

Connecting with others who are safe, attuned and present is the best way to restore a healthy ANS and bring you back into your thrive/ideal state. Engage in activities you know makes you feel better. Look at spending time in nature, practicing yoga, mindfulness, meditation, self-soothing techniques, helping others. Dance, sing and take time to laugh (it releases endorphins). Who else can help? Build habits around your coping behaviours.

4. Reflect and Focus – dedicate time for self-reflective practice

Reflective practice is a process of self-analysis and continuous learning. In this reflective process, focus your attention and deliberately set intentions to support proactive choices for you and your team. Acknowledge what is going well and with kindness to self, look at what can be improved. Proceed with this new information. Reflect when you can – little and often. In the moment, brushing your teeth, walking the dog or even set aside time to have a weekly meeting with yourself. The key is making it a habit.

Figure 3: Notice your polyvagal states and triggers: The bottom-up, top-down and outside-in brain health model (Adapted from Dr. Sarah McKay, 2016)

Remember it is a balancing act!

Remember it is a balancing act!

Awareness is the first step, followed by growth. It’s not about never feeling stressed or uncomfortable but about strengthening and expanding your thrive state/window of tolerance, and ‘building the muscle’ through tools and interventions to feel better resourced to manage own and team challenges.

To conclude: as a leader, having a greater understanding of your own feelings and emotions, recognising your polyvagal states, your triggers and knowing how to support your ideal state and that of your team will be beneficial both, personally and organisationally. If someone asks you, how are you feeling? Really ask yourself, am I ‘fine’ or am I something else?

By creating an environment where your team know how they are feeling, you will create a high-functioning environment and team that will deliver better business results.

If you’d like to find out more about our approach, or about any of our programmes, please contact us.