Global transformation is nigh. Beyond AI and machine learning, or the fact that humans are living longer, the big issue is how humanity is affecting the environment in terms of how we live, how we do business and how compatible our financial and planetary ecosystems may be. With global populations escalating alongside our insatiable appetite for more disposable products, the success of globalisation has started to bear negative side effects on our climate. According to one global consortium of central banks and supervisors (better known as NGFS: Network for Greening the Financial System), recent figures are sobering:

- In 2017, air pollution caused almost five million deaths worldwide.

- In 2018, 62 million people were affected by natural hazards, with two million forced to move home because of climate events.

As individuals, we can all play our part in creating a greener environment. But climate-related risks are also a source of financial risk. That puts them squarely within the mandates of central banks and supervisors charged with ensuring financial stability. And in our view, all banks and financial institutions must also now grasp what the magnitude of climate change heralds for them.

Why focus on finance?

Banks are the key intermediaries which supply funding to industries around the world. They have large exposures to land, buildings, machinery, companies and other assets which could ultimately contribute to climate change. Indeed the Bank of England has highlighted that $20 trillion worth of global assets could be wiped out as a result of climate change.

Action is afoot

In 2018 the financial institutions responsible for managing almost $100 trillion of assets – more than annual worldwide GDP – publicly supported the principle of disclosing material, decision-useful climate-related financial risks by signing up to the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). These recommendations cover four key areas and provide a framework for financial disclosures by companies:

- Governance

- Strategy

- Risk Management

- Metrics and targets

Clarity can be costly

The wholesale reassessment of prospects (no matter what the best intentions are) could destabilise markets, spark a pro-cyclical crystallisation of losses and lead to a persistent tightening of financial conditions. All the more reason to understand the risks and take action now.

What are the key risks?

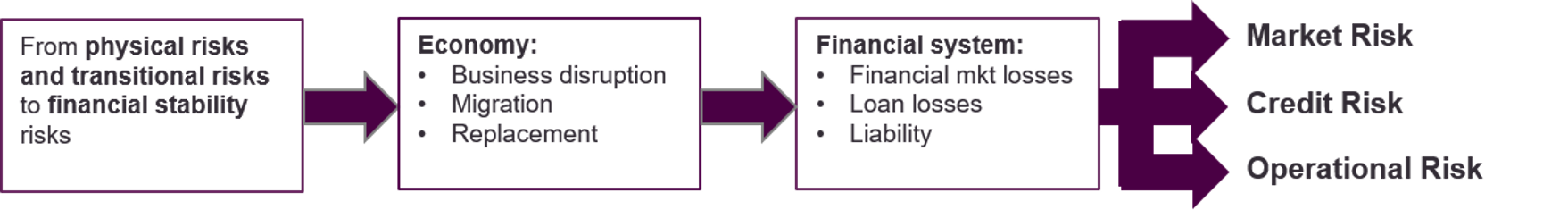

Climate-related financial risks arise from two primary channels: physical and transition.

- Physical risks are associated with the physical effects of climate change such as heatwaves, droughts, floods, storms and rising sea levels. These can potentially result in large financial losses, impairing asset values and the creditworthiness of borrowers, which in turn affect both borrowers and lenders.

- Transition risks are those associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy. These include a spectrum of changes from climate policies and restrictions, to new technologies, to investor sentiment and consumer demands. Individually and collectively, these can each prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets, in particular via impairments, increasing credit exposures and creating additional risks (both market and operational) which again affect both banks and consumers.

Priority challenges

The rise in global average temperatures and sea levels is well documented. This sustained increase in temperature may cause structural shifts in the climate which could lead to water scarcity and declining crop yields. This in turn will cause stress to the agricultural sector and ultimately lead to large financial market losses. Climate change can also be linked to wider macroeconomic impacts such as GDP, inflation, declining productivity, employment, food insecurity, increased mortality and large-scale migrations or political instability.

While we see many banks (and insurance companies) identifying the potential impacts from physical risk factors on areas such as property and real estate, few are identifying the potential impacts from the transition risk itself. Shifting sentiment among customers, and increasing attention and scrutiny from other stakeholders and policy makers, means the pace of the transition may lead to extreme bank vulnerabilities.

Central banks, policy makers and financial regulators have all been vocal on how banks and financial services should manage the possibility of dramatic climate change. There has been a raft of policies, consultations and recommendations proposing guiding principles and approaches, with many leveraging TCFD as their key foundation.

If not managed properly – for instance if markets incorrectly price the risks stemming from extreme weather events – climate risk could hit bank balance sheets with a knock-on effect on financial stability. This will not only require a redesign of traditional risk management frameworks, but also demand a new level of data and reporting, feeding up risks all the way up to the Board. A board-level committee be established (if not already in place) will be essential to ensure Board involvement in the development of appropriate climate change policies, targets and approach and the management of its associated financial risks.

Once those policies are established, they need to be applied to all decision-making layers. That requires a strong procedures framework, with controls and KPIs / KRIs to demonstrate and track progress. The creation of new exclusion policies on sectors (such as lending) which are large contributors to climate change were a good start. The next step will be for forward-looking environmental stress testing and climate change scenario analysis to transition to a world that contains global warming to less than two degrees Celsius – and to a more sustainable business.

If an orderly market transition to a low carbon economy is to be achieved, banks must start minimising their financial risks today and adopt a group-wide climate strategy across the whole bank. Yet many jurisdictions still have no explicit requirement for climate change-related risks to be disclosed by companies as part of mainstream financial filings. Canada is a conspicuous counter-example, with banks publishing comprehensive reports on sustainable finance. This should be the rule, not the exception. Banks must take the lead and look to align their assessment processes and disclosures with the TCFD. Leveraging TCFD’s sector guidance, banks now have the opportunity to step up their engagement with corporate clients to reduce climate risk and redeploy lending to those sectors and companies that are better positioned for a low-carbon future.

Doing the right thing – for all the right reasons

If achieving a sustainable business isn’t enough of an incentive, then the potential to be hit with tens of millions (if not billions) of dollars of losses should be. Over the course of the next few months, we will delve deeper across what a new risk framework should look like (including data, scenarios, models and reporting metrics) along with analysing the potential challenges banks can expect along the way.

We will also explore the opportunities of change – and the positive potential ahead for those banks willing to take action today.